|

| A winter camp high in the Cairngorms |

Another one from the archives. This piece was written for TGO over ten years ago. The advice still stands though so here it is again, with a few modifications (stoves designed for use with inverted canisters didn't exist then, nor did e-readers, smartphones and tablets). Apologies for the wonky formatting - there's a limit to how long I can stand trying to get Blogger to align things!

Winter camping might seem a pursuit for the hardy, the ascetic,

even the masochistic. Severe cold, blizzards and long dark nights sound most

unattractive. With the right skills and equipment winter camping can be

enjoyable though, especially when the frost is sharp, the mountains white with

snow and the skies clear with bright stars shining in the blackness. Lying in a

warm sleeping bag with a mug of hot chocolate watching the winter world is a

wonderful experience. In fact freezing weather is the best for winter camping.

It’s easier to keep warm when it’s dry and cold than when it’s wet and cold. In

Britain wet cold is more common of course and when it rains rather than snows

winter camping can seem just like summer camping, only with longer nights and

cooler temperatures and, a major factor, no midges.

1)

Remember that keeping warm is easier than

getting warm. When you stop to make camp put on

warm dry clothing before you

start to cool down.

2)

Valley bottoms and depressions are likely to

be chillier than hillsides as cold air sinks. Flat areas on the sides of hills

are the warmest places to camp.

|

| A good winter camp site |

3)

Wind whips away warmth. Look for sites

protected from the wind by crags, boulders, banks or trees. A snow shovel can

be used to build snow walls on the windward side of the tent and to heap snow

round the base of the flysheet to reduce the effects of wind.

4)

When camping on deep snow stamp out a

platform then leave it a short while to harden before pitching the tent. This

helps prevent the snow from giving under you when you get in the tent, which

results in a lumpy bed. If you have a snow shovel – which I recommend carrying

when there’s more than a thin cover of snow – then it can be used to flatten

the snow.

|

| Moonlit winter camp with skis and poles used to support tent |

5) Standard tent pegs pull straight out of soft

snow if used as normal. Instead tie the guyline round the peg and bury it

horizontally, stamping the snow down on top. Lengths of cord can be attached to

pegging points without guylines. Better than standard pegs are long wide curved

snow stakes, though these are only worth buying if you snow camp frequently.

Buried pegs will freeze in place and can be hard to dig up. An ice axe helps

with this, though be careful not to damage the tent. An ice axe can also be

used as a tent peg, as can trekking poles and skis.

6) It’s very important to keep moisture out of

the tent. Brush off snow before getting in and strip off any wet garments in

the vestibule.

7) Condensation can be reduced by leaving vents

and, if the weather permits, tent doors open. The tent will be cooler but moist

air will be able to escape.

8)

A candle or gas lantern can help dry out

condensation and also gives off a little warmth. The soft light is soothing

too. Make sure that any burning light is kept well away from tent fabric or any

other flammable items. Keeping a lantern in the vestibule rather than the inner

tent is wise.

9)

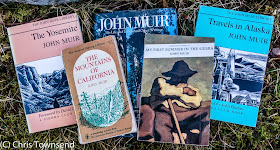

Winter nights are long and dark. An e-reader,

smartphone or tablet for music or radio, paperback book or a pack of cards

helps pass the time.

|

| A comfortable winter camp |

10)

Your sleeping bag can make an excellent warm

garment. If you feel chilly get in it and pull it up under your armpits, using

the shoulder baffle or hood drawcord to keep it in place. In sub zero

temperatures you can cook, eat, read, write and watch the landscape while in

your sleeping bag.

11)

Hot food and drink warms you up so eating and

drinking immediately before going to sleep can help ensure a warm nights sleep.

Fatty foods are good as these release heat slowly and so keep you warm for

longer than sugary ones. Eat plenty too. If you’re hungry you’re more likely to

feel cold.

12)

If you feel chilly during the night and your

sleeping bag is fully done up don some dry clothing. A warm hat and socks can

make a big difference. If there isn’t room in your bag for bulky clothing such

as insulated or heavy fleece jackets spread them over the top.

13)

Most heat is lost to the ground, especially

when it’s frozen or snow covered. If you feel cold where you touch your mat put

clothing under you. If your mat is only a three-quarters length one put clothes

under your feet. Mats that are warm most of the year may not be thick enough

when camping on snow or frozen ground. Two mats are often better. A foam mat

under a self-inflating one is a good combination.

14) When you wake in the morning bring your

clothes inside the sleeping bag to warm them up before you put them on.

|

| Insulating a stove from the snow |

15) Insulate your stove from the ground with a

piece of closed cell foam, the blade of a snow shovel or even a book. If the

fuel canister or bottle is separate from the stove insulating it is more

important than insulating the stove.

16) Butane/propane gas doesn’t vaporise well in

below freezing temperatures so many gas stoves can be very slow or even not

work at all. The best for winter use are ones where the canister can be

inverted to turn them into liquid feed stoves. With other stoves heat output can

be increased by warming cartridges inside clothing or your sleeping bag. You

can warm them by putting your hands round them when they are being used too –

it’s best to wear thin gloves when doing this as cartridges can get very cold. Heat

exchanger pots also speed up boiling and snow melting times. Meths, petrol and

paraffin all work fine in the cold though the first can be slow when melting

snow.

|

| An inverted canister stove |

17) Avoid melting snow whenever possible, as it

takes a long time and uses lots of fuel (as much heat is needed to produce a

litre of water from snow as to boil that water). Dig down to a stream or pool

if the snow is really deep or look for open sections. Carrying water a half

mile or so is still quicker than melting snow. Take care not to fall in when

collecting water.

18)

When melting snow put a little water in the

bottom of the pan first. Otherwise the pan may scorch and the water will taste

burnt. If you haven’t any water start with a small amount of snow and stir it

rapidly until it melts. Don’t pack a pan tightly with snow – this will soak up

any water and then the pan with burn.

19)

Water will freeze overnight unless insulated

from the cold. Fill thermos flasks in the evening so you don’t have to melt

snow in the morning. Water bottles can be insulated by wrapping them in

clothing and keeping them off the ground. In your rucksack or in your boots are

good places. Standing bottles upside down means the mouth shouldn’t freeze even

if some of the water does. Wide mouthed bottles are best in winter as any ice

that forms can easily be shaken out. Insulating covers for water bottles can be

made from duct tape and closed cell foam. If the snow is deep burying your

water bottles in it will stop the water from freezing as snow insulates well.

Fill pans with water during the evening. If the water freezes just pop the pan

on the stove to thaw it out. Breakfast cereals like porridge oats or muesli can

be added to the water in the evening and then cooked in the morning.

20)

Use a pee bottle so you don’t have to leave

the tent during the night. Make sure it’s marked clearly so it isn’t mistaken

for a water bottle. When you pee into snow cover the place up as yellow snow

looks unsightly. Digging through deep snow or frozen ground to make a toilet

pit may not be possible (though an ice axe can break up the latter). Consider

packing out faeces in doubled plastic bags. If you do leave faeces on the

ground site your toilet well away from any water sources (check with the map if

these aren’t visible), anywhere someone might camp and any footpaths. Burn or

pack out toilet paper or else use snow.